Somali leaders have not asked themselves the question Somalia’s first generation of political leaders had failed to ask about territorial disputes. On Somalia’s case for seeking to gain control of “missing territories” Bahru Zewde, the author of A History of Modern Ethiopia 1855-1991, writes:

“Diplomatically, however, the cause of Somali irredentism was doomed. In the African context in particular, the Organization of African unity, founded in 1963, for understandable reasons reaffirmed the inviolability of international borders, however arbitrarily they might have been drawn in the past ” (Zewde, p.192; 2001).

Although Somaliland claims the territory on account of it being a part of ex-British Somaliland it has never addressed the plight of the people in the territory the International Community has designated as disputed territories. British support for Somaliland political institutions and economic development only benefits social groups that signed Protectorate agreements and live in non-disputed territories . A large part of the disputed territory is home to people whom the British colonial administrators did not include in the “Proclamation of Terminating Her Majesty’s Protection Over the Somaliland Protectorate.” London Gazette published on 24 June 1960 implicitly states the distinction the British government made between subjects from clans in the Protectorate and the clans from non-Protectorate territories:

“Now, therefore, We do hereby, by and with the advice of our Privy Council, proclaim and declare that, as from the beginning of the appointed day between Us or Our Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and any of the Tribes of the said territories, all Our obligations existing immediately before that day towards the said territories and all functions, powers, rights, authority or jurisdiction exercisable by Us immediately before that day in or in relation to the said territories by treaty, grant, usage, sufferance or otherwise, shall lapse.”

|

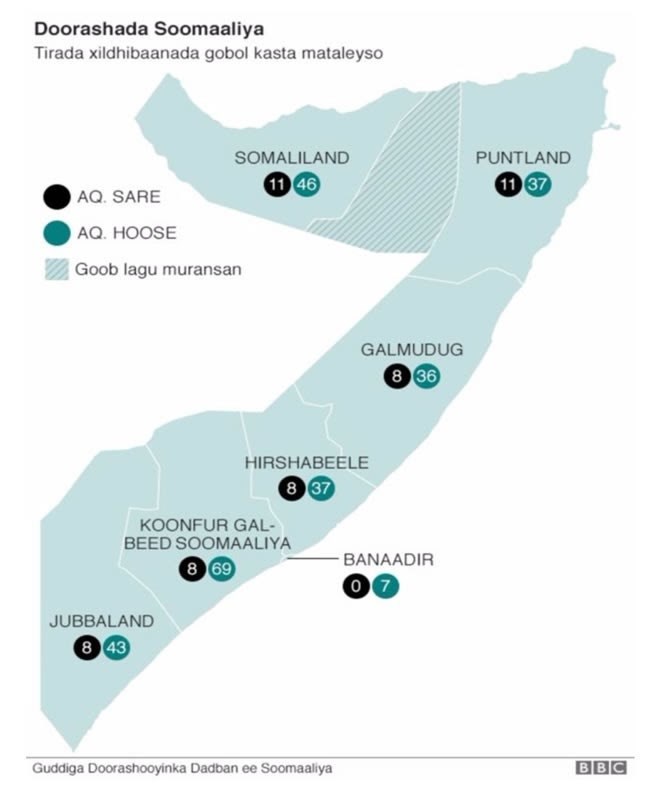

Somaliland is not only in territorial dispute with Puntland, a federal member state. A few weeks ago when the Planning Minister of the Federal Government of Somalia paid a visit to Badhan, the Somaliland Minister for foreign Affairs accused Somalia of violating “territorial integrity of Somaliland”. Somaliland claims disputed territories on the basis of a colonial border before the Union ( 1 July 1960 ), whereas Puntland retains the privilege to appoint federal MPs and Senators from disputed territories, as the contentious electoral map developed by UNSOM in 2016 shows. In this situation neither political representatives from disputed territories based either in Hargeisa or in Garowe are capable of addressing the plight people in “Eastern Somaliland” without Britain’s commitment to “enhancing political stability in Somalia,including in Somaliland.” Britain is “supportive of dialogue between Somaliland andneighbouring Puntland, and with the Federal Government of Somalia on areas ofmutual interest.”

UNSOM map showing “disputed territories”

A war between Somaliland and Puntland will prolong the suffering of people in disputed territories. Despite Somaliland government’s indifference to the plight of people it looks upon as citizens, it has a major advantage over Puntland, which is claiming disputed territories on the basis of shared clan affiliation and the 1998 Puntland Charter. Puntland invoked the Charter for federal representation priveleges during negotiations with the Somali Federal Government before the 2017 election in Mogadishu.

Since 2009 the International Community has used different approaches such as the dual track policy to diffuse tensions periodically triggered by the territorial dispute between Puntland and Somaliland.

Britain’s development assistance and scholarships to Somalia hardly reach people in the disputed territories. As the country that facilitated end of the transition in Somalia and generously contributes to AMISOM budget, Britain has the diplomatic influence to facilitate talks between stakeholders in the disputed territories. A threat of war makes disputed territories inaccessible to aid workers, and youths vulnerable to radicalisation.

The disadvantage imposed by disputed territories status on people is more pronounced in areas such as Lasanod, Huddun and Taleh, where people cast their votes during 2017 Somaliland elections but will never enjoy benefits the successfully conducted election will create in the form more development assistance for non-disputed territories in the ex-British Somaliland, and soon to be enhanced Somaliland Compact.

Both the arguments for a clan-based adminstraton (Puntland) and pre-indendence identity (Somaliland) are failing people in the disputed territories.

Liban Ahmad

libahm@icloud.com